Like many of its competitors, Bear Stearns saw the rise of the hedge fund industry during the 1990s and began managing its own funds with outside investor capital under the name Bear Stearns Asset Management (BSAM). Unlike its competitors, Bear hired all of its fund managers internally, with each manager specializing in a particular security or asset class. Objections by some Bear executives, such as co-president Alan Schwartz, that such concentration of risk could raise volatility were ignored, and the impressive returns posted by internal funds such as Ralph Cioffi’s High-Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund quieted any concerns.

Cioffi’s fund was invested in sophisticated credit derivatives backed by mortgage securities. When the housing bubble burst, he redoubled his bets, raising a new Enhanced Leverage High-Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund that would use 100 leverage (as compared to the 35 leverage employed by the original fund). The market continued to turn disastrously against the fund, which was soon stuck with billions of dollars worth of illiquid, unprofitable mortgages. In an attempt to salvage the situation and cut his losses, Cioffi launched a vehicle named Everquest Financial and sold its shares to the public. But when journalists at the Wall Street Journal revealed that Everquest’s primary assets were the “toxic waste” of money-losing mortgage securities, Bear had no choice but to cancel the public offering. With spectacular losses mounting daily, investors attempted to withdraw their remaining holdings. In order to free up cash for such redemptions, the fund had to liquidate assets at a loss, selling that only put additional downward pressure on its already underwater positions. Lenders to the fund began making margin calls and threatening to seize its $1.2 billion in collateral.

In a less turbulent market it might have worked, but the subprime crisis had spent weeks on the front page of financial newspapers around the globe, and every bank on Wall Street was desperate to reduce its own exposure. Insulted and furious that Bear had refused to inject any of its own capital to save the funds, Steve Black, J.P. Morgan Chase head of investment banking, called Schwartz and said, “We’re defaulting you.”

The default and subsequent seizure of $400 million in collateral by Merrill Lynch proved highly damaging to Bear Stearns’s reputation across Wall Street. In a desperate attempt to save face under the scrutiny of the SEC, James Cayne made the unprecedented move of using $1.6 billion of Bear’s own capital to prop up the hedge funds. By late July 2007 even Bear’s continued support could no longer prop up Cioffi’s two beleaguered funds, which paid back just $300 million of the credit its parent had extended. With their holdings virtually worthless, the funds had no choice but to file for bankruptcy protection.

On November 14, just two weeks after the Journal story questioning Cayne’s commitment and leadership, Bear Stearns reported that it would write down $1.2 billion in mortgage- related losses. (The figure would later grow to $1.9 billion.) CFO Molinaro suggested that the worst had passed, and to outsiders, at least, the firm appeared to have narrowly escaped disaster.

Behind the scenes, however, Bear management had already begun searching for a white knight, hiring Gary Parr at Lazard to examine its options for a cash injection. Privately, Schwartz and Parr spoke with Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. founder Henry Kravis, who had first learned the leveraged buyout market while a partner at Bear Stearns in the 1960s. Kravis sought entry into the profitable brokerage business at depressed prices, while Bear sought an injection of more than $2 billion in equity capital (for a reported 20% of the company) and the calming effect that a strong, respected personality like Kravis would have upon shareholders. Ultimately the deal fell apart, largely due to management’s fear that KKR’s significant equity stake and the presence of Kravis on the board would alienate the firm’s other private equity clientele, who often competed with KKR for deals. Throughout the fall Bear continued to search for potential acquirers. With the market watching intently to see if Bear shored up its financing, Cayne managed to close only a $1 billion cross-investment with CITIC, the state-owned investment company of the People’s Republic of China.

Bear’s $0.89 profit per share in the first quarter of 2008 did little to quiet the growing whispers of its financial instability. It seemed that every day another major investment bank reported mortgage-related losses, and for whatever reason Bear’s name kept cropping up in discussions of the by-then infamous subprime crisis. Exacerbating Bear’s public relations problem, the SEC had launched an investigation into the collapse of the two BSAM hedge funds, and rumors of massive losses at three major hedge funds further rattled an already uneasy market. Nonetheless, Bear executives felt that the storm had passed, reasoning that its almost $21 billion in cash reserves had convinced the market of its long-term viability.

Instead, on Monday, March 10, 2008, Moody’s downgraded 163 tranches of mortgage- backed bonds issued by Bear across fifteen transactions. The credit rating agency had drawn sharp criticism for its role in the subprime meltdown from analysts who felt the company had overestimated the creditworthiness of mortgage-backed securities and failed to alert the market of the danger as the housing market turned. As a result, Moody’s was in the process of downgrading nearly all of its ratings, but as the afternoon wore on, Bear’s stock price seemed to be reacting far more negatively than those of competitor firms.

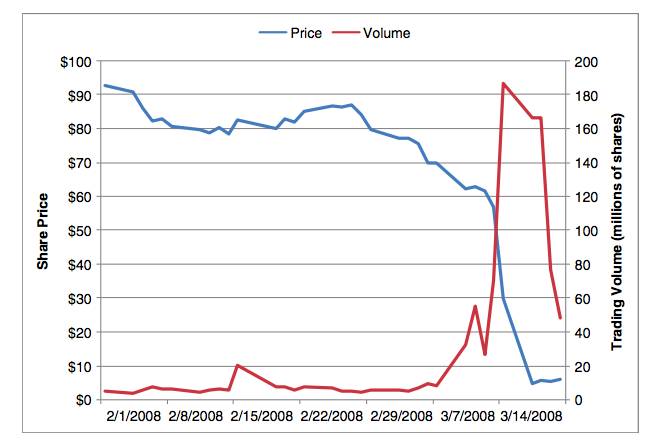

Wall Street’s drive toward ever more sophisticated communications devices had created an interconnected network of traders and bankers across the world. On most days, Internet chat and mobile e-mail devices relayed gossip about compensation, major employee departures, and even sports betting lines. On the morning of March 10, however, they were carrying one message to the exclusion of all others: Bear was having liquidity problems. At noon, CNBC took the story public on Power Lunch. As Bear’s stock price fell more than 10 percent to $63, Ace Greenberg frantically placed calls to various executives, demanding that someone publicly deny any such problems. When contacted himself, Greenberg told a CNBC correspondent that the rumors were “totally ridiculous,” angering CFO Molinaro, who felt that denying the rumor would only legitimize it and trigger further panic selling, making prophecies of Bear’s illiquidity self-fulfilling. Just two hours later, however, Bear appeared to have dodged a bullet. News of New York governor Eliot Spitzer’s involvement in a high-class prostitution ring wiped any financial rumors off the front page, leading Bear executives to believe the worst was once again behind them.

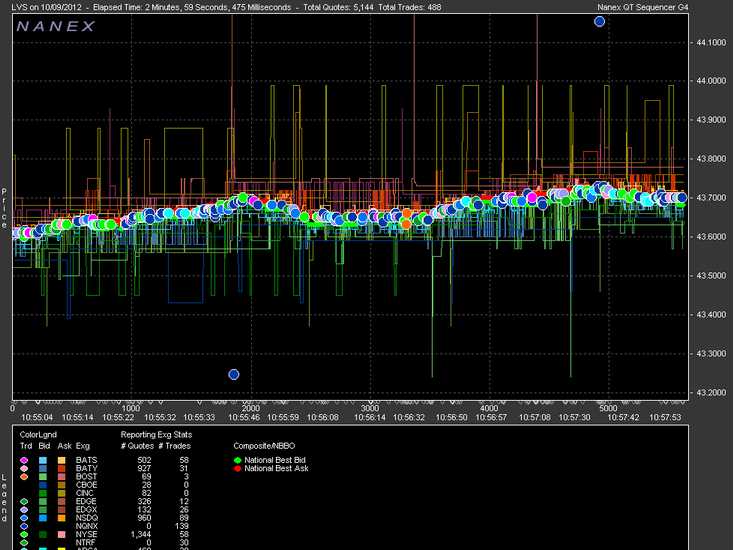

Instead, the rumors exploded anew the next day, as many interpreted the Federal Reserve’s announcement of a new $200 billion lending program to help financial institutions through the credit crisis as aimed specifically toward Bear Stearns. The stock dipped as low as $55.42 before closing at $62.97. Meanwhile, Bear executives faced a new crisis in the form of an explosion of novation requests, in which a party to a risky contract tries to eliminate its risky position by selling it to a third party. Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, and Goldman Sachs all reported a deluge of novation requests from firms trying to reduce their exposure to Bear’s credit risk. The speed and force of this explosion of novation requests meant that before Bear could act, both Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse issued e-mails to their traders holding up any requests relating to Bear Stearns pending approval by their credit departments. Once again, the electronically linked gossip network of trading desks around the world dealt a blow to investor confidence in Bear’s stability, as a false rumor circulated that Credit Suisse’s memo had forbidden its traders from engaging in any trades with Bear. The decrease in confidence in Bear’s liquidity could be quantified by the rise in the cost of credit default swaps on Bear’s debt. The price of such an instrument – which effectively acts as five years of insurance against a default on $10 million of Bear’s debt – spiked to more than $626,000 from less than $100,000 in October, indicating heavy betting by some firms that Bear would be unable to pay its liabilities.

Internally, Bear debated whether to address the rumors publicly, ultimately deciding to arrange a Wednesday morning interview of Schwartz by CNBC correspondent David Faber. Not wanting to encourage rumors with a hasty departure, Schwartz did the interview live from Bear’s annual media conference in Palm Beach. Chosen because of his perceived friendliness to Bear, Faber nonetheless opened the interview with a devastating question that claimed direct knowledge of a trader whose credit department had temporarily held up a trade with Bear. Later during the interview Faber admitted that the trade had finally gone through, but he had called into question Bear’s fundamental capacity to operate as a trading firm. One veteran trader later commented,

You knew right at that moment that Bear Stearns was dead, right at the moment he asked that question. Once you raise that idea, that the firm can’t follow through on a trade, it’s over. Faber killed him. He just killed him.

Despite sentiment at Bear that Schwartz had finally put the company’s best foot forward and refuted rumors of its illiquidity, hedge funds began pulling their accounts in earnest, bringing Bear’s reserves down to $15 billion. Additionally, repo lenders – whose overnight loans to investment banks must be renewed daily – began informing Bear that they would not renew the next morning, forcing the firm to find new sources of credit. Schwartz phoned Parr at Lazard, Molinaro reviewed Bear’s plans for an emergency sale in the event of a crisis, and one of the firm’s attorneys called the president of the Federal Reserve to explain Bear’s situation and implore him to accelerate the newly announced program that would allow investment banks to use mortgage securities as collateral for emergency loans from the Fed’s discount window, normally reserved for commercial banks.

The trickle of withdrawals that had begun earlier in the week turned into an unstoppable torrent of cash flowing out the door on Thursday. Meanwhile, Bear’s stock continued its sustained nosedive, falling nearly 15% to an intraday low of $50.48 before rallying to close down 1.5%. At lunch, Schwartz assured a crowded meeting of Bear executives that the whirlwind rumors were simply market noise, only to find himself interrupted by Michael Minikes, senior managing director,

Do you have any idea what is going on? Our cash is flying out the door! Our clients are leaving us!

Hedge fund clients jumped ship in droves. Renaissance Technologies withdrew approximately $5 billion in trading accounts, and D. E. Shaw followed suit with an equal amount. That evening, Bear executives assembled in a sixth-floor conference room to survey the carnage. In less than a week, the firm had burned through all but $5.9 billion of its $18.3 billion in reserves, and was still on the hook for $2.4 billion in short-term debt to Citigroup. With a panicked market making more withdrawals the next day almost certain, Schwartz accepted the inevitable need for additional financing and had Parr revisit merger discussions with J.P. Morgan Chase CEO James Dimon that had stalled in the fall. Flabbergasted at the idea that an agreement could be reached that night, Dimon nonetheless agreed to send a team of bankers over to analyze Bear’s books.

Parr’s call interrupted Dimon’s 52nd birthday celebration at a Greek restaurant just a few blocks away from Bear headquarters, where a phalanx of attorneys had begun preparing emergency bankruptcy filings and documents necessary for a variety of cash-injecting transactions. Facing almost certain insolvency in the next 24 hours, Schwartz hastily called an emergency board meeting late that night, with most board members dialing in remotely. Bear’s nearly four hundred subsidiaries would make a bankruptcy filing impossibly complicated, so Schwartz continued to cling to the hope for an emergency cash infusion to get Bear through Friday. As J.P. Morgan’s bankers pored over Bear’s positions, they balked at the firm’s precarious position and the continued size of its mortgage holdings, insisting that the Fed get involved in a bailout they considered far too risky to take on alone.

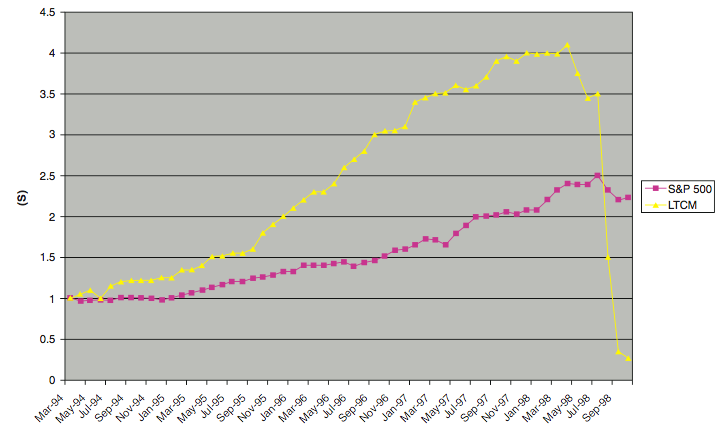

Its role as a counterparty in trillions of dollars’ worth of derivatives contracts bore an eerie similarity to LTCM, and the Fed once again saw the potential for financial Armageddon if Bear were allowed to collapse of its own accord. An emergency liquidation of the firm’s assets would have put strong downward pressure on global securities prices, exacerbating an already chaotic market environment. Facing a hard deadline of credit markets’ open on Friday morning, the Fed and J.P. Morgan wrangled back and forth on how to save Bear. Working around the clock, they finally reached an agreement wherein J.P. Morgan would access the Fed’s discount window and in turn offer Bear a $30 billion credit line that, as dictated by a last-minute insertion by J.P. Morgan general counsel Steven Cutler, would be good for 28 days. As the press release went public, Bear executives cheered; Bear would have almost a month to seek alternative financing.

Where Bear had seen a lifeline, however, the market saw instead a last desperate gasp for help. Incredulous Bear executives could only watch in horror as the firm’s capital continued to fly out of its coffers. On Friday morning Bear burned through the last of its reserves in a matter of hours. A midday conference call in which Schwartz confidently assured investors that the credit line would allow Bear to continue “business as usual” did little to stop the bleeding, and its stock lost almost half of its already depressed value, closing at $30 per share.

All day Friday, Parr set about desperately trying to save his client, searching every corner of the financial world for potential investors or buyers of all or part of Bear. Given the severity of the situation, he could rule out nothing, from a sale of the lucrative prime brokerage operations to a merger or sale of the entire company. Ideally, he hoped to find what he termed a “validating investor,” a respected Wall Street name to join the board, adding immediate credibility and perhaps quieting the now deafening rumors of Bear’s imminent demise. Sadly, only a few such personalities with the reputation and war chest necessary to play the role of savior existed, and most of them had already passed on Bear.

Nonetheless, Schwartz left Bear headquarters on Friday evening relieved that the firm had lived to see the weekend and secured 28 days of breathing room. During the ride home to Greenwich, an unexpected phone call from New York Federal Reserve President Timothy Geithner and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson shattered that illusion. Paulson told a stunned Schwartz that the Fed’s line of credit would expire Sunday night, giving Bear 48 hours to find a buyer or file for bankruptcy. The demise of the 28-day clause remains a mystery; the speed necessary early Friday morning and the inclusion of the clause by J.P. Morgan’s general counsel suggest that Bear executives had misinterpreted it, although others believe that Paulson and Geithner had soured both on Bear’s prospects and on market perception of an emergency loan from the Fed as Friday wore on. Either way, the Fed had made up its mind, and a Saturday morning appeal from Schwartz failed to sway Geithner.

All day Saturday prospective buyers streamed through Bear’s headquarters to pick through the rubble as Parr attempted to orchestrate Bear’s last-minute salvation. Chaos reigned, with representatives from every major bank on Wall Street, J. C. Flowers, KKR, and countless others poring over Bear’s positions in an effort to determine the value of Bear’s massive illiquid holdings and how the Fed would help in financing. Some prospective buyers wanted just a piece of the dying bank, others the whole firm, with still others proposing more complicated multiple-step transactions that would slice Bear to ribbons. One by one, they dropped out, until J. C. Flowers made an offer for 90% of Bear for a total of up to $2.6 billion, but the offer was contingent on the private equity firm raising $20 billion from a bank consortium, and $20 billion in risky credit was unlikely to appear overnight.

That left J.P. Morgan. Apparently the only bank willing to come to the rescue, J.P. Morgan had sent no fewer than 300 bankers representing 16 different product groups to Bear headquarters to value the firm. The sticking point, as with all the bidders, was Bear’s mortgage holdings. Even after a massive write-down, it was impossible to assign a value to such illiquid (and publicly maligned) securities with any degree of accuracy. Having forced the default of the BSAM hedge funds that started this mess less than a year earlier.

On its final 10Q in March, Bear listed $399 billion in assets and $387 billion in liabilities, leaving just $12 billion in equity for a 32 leverage multiple. Bear initially estimated that this included $120 billion of “risk-weighted” assets, those that might be subject to subsequent write-downs. As J.P. Morgan’s bankers worked around the clock trying to get to the bottom of Bear’s balance sheet, they came to estimate the figure at nearly $220 billion. That pessimistic outlook, combined with Sunday morning’s New York Times article reiterating Bear’s recent troubles, dulled J.P. Morgan’s appetite for jumping onto what appeared to be a sinking ship. Later, one J.P. Morgan banker shuddered, recalling the article. “That article certainly had an impact on my thinking. Just the reputational aspects of it, getting into bed with these people.”

On Saturday morning J.P. Morgan backed out and Dimon told a shell-shocked Schwartz to pursue any other option available to him. The problem was, no such alternative existed. Knowing this, and the possibility that the liquidation of Bear could throw the world’s financial markets into chaos, Fed representatives immediately phoned Dimon. As it had in the LTCM case a decade ago, the Fed relied heavily on suasion, or “jawboning,” the longtime practice of attempting to influence market participants by appeals to reason rather than a declaration by fiat. For hours, J.P. Morgan’s and the Fed’s highest-ranking officials played a game of high-stakes poker, with each side bluffing and Bear’s future hanging in the balance. The Fed wanted to avoid unprecedented government participation in the bailout of a private investment firm, while J.P. Morgan wanted to avoid taking on any of the “toxic waste” in Bear’s mortgage holdings. “They kept saying, ‘We’re not going to do it,’ and we kept saying, ‘We really think you should do it,’” recalled one Fed official. “This went on for hours . . . They kept saying, ‘We can’t do this on our own.’” With the hours ticking away until Monday’s Australian markets would open at 6:00 p.m. New York time, both sides had to compromise.

On Sunday afternoon, Schwartz stepped out of a 1:00 emergency meeting of Bear’s board of directors to take the call from Dimon. The offer would come somewhere in the range of $4 to 5 per share. Hearing the news from Schwartz, the Bear board erupted with rage. Dialing in from the bridge tournament in Detroit, Cayne exploded, ranting furiously that the firm should file for bankruptcy protection under Chapter 11 rather than accept such a humiliating offer, which would reduce his 5.66 million shares – once worth nearly $1 billion – to less than $30 million in value. In reality, however, bankruptcy was impossible. As Parr explained, changes to the federal bankruptcy code in 2005 meant that a Chapter 11 filing would be tantamount to Bear falling on its sword, because regulators would have to seize Bear’s accounts, immediately ceasing the firm’s operations and forcing its liquidation. There would be no reorganization.

Even as Cayne raged against the $4 offer, the Fed’s concern over the appearance of a $30 billion loan to a failing investment bank while American homeowners faced foreclosures compelled Treasury Secretary Paulson to pour salt in Bear’s wounds. Officially, the Fed had remained hands-off in the LTCM bailout, relying on its powers of suasion to convince other banks to step up in the name of market stability. Just 10 years later, they could find no takers. The speed of Bear’s collapse, the impossibility of conducting true due diligence in such a compressed time frame, and the incalculable risk of taking on Bear’s toxic mortgage holdings scared off every buyer and forced the Fed from an advisory role into a principal role in the bailout. Worried that a price deemed at all generous to Bear might subsequently encourage moral hazard – increased risky behavior by investment banks secure in the knowledge that in a worst-case scenario, disaster would be averted by a federal bailout – Paulson determined that the transaction, while rescuing the firm, also had to be punitive to Bear shareholders. He called Dimon, who reiterated the contemplated offer range.

“That sounds high tome,” Paulson told the J.P. Morgan chief. “I think this should be done at a very low price.” It was moments later that Braunstein called Parr. “The number’s $2.” Under Delaware law, executives must act on behalf of both shareholders and creditors when a company enters the “zone of insolvency,” and Schwartz knew that Bear had rocketed through that zone over the past few days. Faced with bankruptcy or J.P. Morgan, Bear had no choice but to accept the embarrassingly low offer that represented a 97% discount off its $32 close on Friday evening. Schwartz convinced the weary Bear board that $2 would be “better than nothing,” and by 6:30 p.m., the deal was unanimously approved.

After 85 years in the market, Bear Stearns ceased to exist.